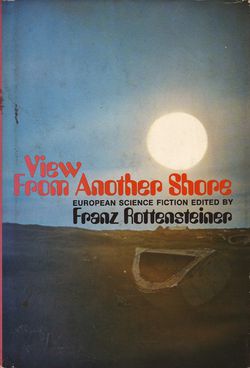

A fragment from the introduction of “View From Another Shore. European Science Fiction”, edited by Franz Rottensteiner, Liverpool University Press, 1999; (First edition : Seabury Press, 1973, New York)

A fragment from the introduction of “View From Another Shore. European Science Fiction”, edited by Franz Rottensteiner, Liverpool University Press, 1999; (First edition : Seabury Press, 1973, New York)

“I think that the great difference between the mass of American SF and the (very rare) European masterpieces is their degree of seriousness, moral seriousness. Best exemplified perhaps by Frederik Pohl’s “Gateway” novels and the Strugatskys’ “Roadside Picnic”.

“Roadside Picnic” is in essence an existential novel about fighting on and keeping your moral integrity in a corrupt world where life is constant fight for survival. Pohl’s novels are simply about winning in the lottery, hitting the jackpot. It may cost your life, but the rewards for winning are tremendous, and the universe is full of gifts.

The Strugatskys adopt fairy tale motifs, but their stories are the realistic ones, and Pohl’s the fairy tales.” – Franz Rottensteiner in an interview with Will Scofield

“The Euros might have invented SF, but it was mostly US Americans that ran with it and dominate it even today. Sounds more sour grapes. Translation: “Hello. I am a snooty self-proclaimed intellectual from Europe. Watch as I demolish this straw man of my own devising then gaze into the abyss of my own navel.” America Will be Greeaat Again. Yuuuge. Faaantestik !” – Donald Duck (?)

“International SF” is an illusion ; the only truly international science fiction is bad science fiction whose clichés are the same no matter where they are written.” – Franz Rottensteiner

Franz Rottensteiner : “Science fiction is a branch of literature that tries to push the borders of the unknown out a little further.

It attempts to unveil the future ; to imagine worlds lying beyond the next hill, river or ocean (including the ocean of space) ; to impress vividly upon the reader that the world need to necessarily be the way it happens to be, and that other states of existence are possible besides the one we know.

Change is the proclaimed credo of science fiction – so much that some writers have claimed this essential characteristic to be something that distinguishes SF above all other kinds of fiction.

How paradoxical, then, that science fiction should be primarily an English-language phenomenon, at least in the minds of the majority of readers – in Europe as well.

One German commentator even went so far as to call SF “the American fairy tale”.

A casual observer should expect science fiction to be more international than other kinds of popular fiction, precisely as a result of this stress on change : for isn’t reasonable to assume that the hopes, fears and expectations of people will be different in different countries, their ways of looking at things unlike those in our own country ?

And yet the facts point to a different picture ; while change is welcomed, obviously not all kinds of change are welcomed : not, for instance, the change that is necessary to adjust to the worlds presented in foreign science fiction.

In the United States, SF translations from foreign languages in recent times hardly exceed several dozen, and for the most part these are taken from only two language islands : Russia and France.

The rest consists mostly of works by writers primarily known for their achievements outside the boundaries of science fiction. Nor is the situation much better in the various European countries, aside from Russia and Eastern Europe which had their large independent body of science fiction.

At least eighty to ninety percent of all science fiction published in countries such as France, Germany, Italy, Spain, the Netherlands, Sweden, Norway or Denmark consist of American and British science fiction.

Is this entirely due to the superior quality of English-language science fiction ?

Most readers would probably think so, as a quote from one of the veteran editors in the field testifies :

“We science fiction readers whose native language happens to be ENGLISH – that is to say we American, we Canadian, we British, we Australian, we New Zealander science fiction readers – tend to a curious sort of provincialism in our thinking regarding the boundaries of science fiction.

We tend to think that all that is worth reading and all that is worth noticing is naturally written in ENGLISH.

In our conventions and our awards and our discussions we slip into the habit of referring to our favorites as the World’s Best this and the World’s Best that.” – Donald Wolheim in his introduction to Sam.J.Lundwall‘s “Science Fiction : What It’s All About”, New York ; Ace Books, 1971

While it must be admitted that the quality of the better American SF is higher that of the majority of European works I know in the genre, this is certainly isn’t true when we turn to the top level.

The main reason for the obscurity of European SF, however, seems to me to be the language problem, and the economic results following from it.

English is readily understood almost everywhere in the world, for most educated Europeans it serves as a second language, and this familiarity ensures writings in that language a ready acceptance.

Editors prefer to bring out works they can read and evaluate themselves ; and how many SF editors in the U.S. (or U.K.) can read at least one language of the many spoken and written in Europe ?

And to gain a reasonably accurate impression of what is going on in European SF, they – and European SF editors – would have to understand many more than just one European language. As far as publisher’s readers are concerned, they are hard to find and expensive, and you can never trust their judgment as you an your own.

Much the same goes for translators.

For one person able to translate from Russian, you can find about one hundred for English ; for some other languages it is even more difficult to find qualified translators.

These facts, combined with the large quantity of science fiction available from Anglo-Saxon countries, and the prevalent belief in its superiority, are quite sufficient to explain why European science fiction is so relatively unknown even in Europe.

In addition, the majority of science fiction books hardly sell to publishers because of the strenghts of the invidual books; they sell as part of the “SF” package – just as many westerns, mysteries and other genre titles are purchased by publishers.

Few editors and publishers are willing to consider European works, even if of superior quality, when so much is available in a language that poses no problems in evaluation and translation.…

Events as EUROCONS have helped to promote contact between the various European SF landscapes, and to draw the attention of American aficionados to the existence of a science fiction that has developed apart from the “mainstream” of American science fiction, although not wholly uninfluenced by or isolated from it…

For, whatever modern science fiction may be, and whatever importance one may attribute to the founding of Amazing Stories (the first sf magazine in the world) in 1926 and the specialization that followed from it, the existence of a separate tradition of European SF can hardly be denied.

And it wasn’t only Jules Verne and Karel Čapek who made important contributions to the development and history of science fiction in Europe.

In some cases only the language barrier – the fact that they lived in a “linguistic trap” (as Stanisław Lem puts it) – has prevented the recognition of other euro-continental writers”

“International SF” is an illusion ; the only truly international science fiction is bad science fiction whose clichés are the same no matter where they are written.

Good European SF writing contains features that are uniquely its own, and the works of writers such as Stanisław Lem, A. and B. Strugatsky and Herbert W.Franke, seem to me unmistakably European.

It is perhaps a matter of philosophy, of seriousness of purpose, as opposed to the irrelevance and playfulness of most American SF.

These writers deal with real problems, and they come to grips with the problems posed.

European SF is different from the stories that are to be found in any American SF magazine or anthology. Different, but good.”

©Franz Rottensteiner

Reproduced with the permission of the author and the publisher. We’re thanking them.

Franz Rottensteiner (born in Waidmannsfeld, Lower Austria, Austria, on 18 January 1942) is an Austrian critic, editor and literary agent in the fields of science fiction and the fantastic.

Franz Rottensteiner (born in Waidmannsfeld, Lower Austria, Austria, on 18 January 1942) is an Austrian critic, editor and literary agent in the fields of science fiction and the fantastic.

Rottensteiner studied journalism, English and history at the University of Vienna, receiving his doctorate in 1969.

He served about fifteen years as librarian and editor at the Österreichisches Institut für Bauforschung (Austrian Institute of Construction) in Vienna.

In addition, he produced a number of translations into German of leading SF authors, including Herbert W. Franke, Stanislaw Lem, Philip K. Dick, Kobo Abe, Cordwainer Smith, Brian W. Aldiss and the Strugatsky brothers.

He has edited the SF of the World series for Insel Verlag, the Fantastic Novels series for Paul Zsolnay Verlag, and the Fantastic Library series – now over 250 volumes – for Suhrkamp Verlag.

He writes in English as well as in German, his critical articles having appeared in Science Fiction Studies and elsewhere. His criticism is intelligent, polemical and left-wing, and best expressed in fairly academic formats.

He is particularly well known for his spirited promotion of the work of Stanisław Lem, for whom he long served as literary agent, and for the contempt he has often expressed for much Genre SF.

In 1973 his New York anthology “View From Another Shore” of European science fiction introduced a number of continental authors to the English-reading public. Some of the authors in the work are Stanislaw Lem, Josef Nesvadba, Gerard Klein and Jean-Pierre Andrevon.

The year 1975 saw the start of his series “Die phantastischen Romane” (Fantastic Novels). For seven years it re-published works of both lesser-and better-known writers as well as new ones, ending with a total of 28 volumes. In the years 1979-1985 he brought out translations of H. G. Wells’s works in an eighteen volumes series.

Rottensteiner provoked some controversy with his assessment of American science fiction; “what matters is the highest achievements, and there the US has yet to produce a figure comparable to H.G. Wells, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek or Stanisław Lem.”

Rottensteiner described Roger Zelazny, Barry N. Malzberg, and Robert Silverberg as producing “travesties of fiction” and stated “Asimov is a typical non-writer, and Heinlein and Anderson are just banal“. However, Rottensteiner praised Philip K. Dick, listing him as one of “the greatest SF writers”.

From 1980 through 1998 he was advisor for Suhrkamp Press’ Phantastische Bibliothek (Fantastic Library), which brought out some three hundred books.

In all, he has edited about fifty anthologies, produced two illustrated books (The Science Fiction Book : An Illustrated History (New York: Seabury Press, 1975), “The Fantasy Book : The Ghostly, the Gothic, the Magical, the Unreal” (London: Thames and Hudson, 1978); vt “The Fantasy Book: An Illustrated History from Dracula to Tolkien” (New York: Collier, 1978) as well as working on numerous reference works on science fiction.

Franz Rottensteiner is known his collection of “literary” fantasies by Jorge Luis Borges and others, “The Slaying of the Dragon: Modern Tales of the Playful Imagination” (anth 1984) and for “Microworlds: Writings on Science Fiction” (coll 1984 by Lem), edited and introduced by Rottensteiner. His close association with and promotion of Lem until 1995 was a factor in the recognition of the latter in the United States.

Many of his critical writings in German first appeared in his own high-quality Fanzine, “Quarber Merkur”, from which the book Quarber Merkur (anth 1979) was collected.

“Quarber Merkur” is the leading German language critical journal of science fiction, since 1963. In 2004, on the occasion of the hundredth number of this journal, he was awarded a special Kurd-Laßwitz Award.

Two books of essays edited by Rottensteiner are “Über H.P. Lovecraft” (On H.P. Lovecraft, anth 1984), and “Die dunkle Seite der Wirklichkeit” (The Dark Side of Reality, anth 1987).

From 1989 he edited a serial guide in loose-leaf form in binders, which had reached 1250pp by February 1991: “Werkführer durch die utopisch-phantastiche Literatur” (Work Guide to Utopian and Fantastic Literature).

Works :

“The Best of Austrian Science Fiction” (Studies in Austrian Literature, Culture, and Thought. Translation Series, Aug., 2001) by Franz Rottensteiner and Todd C. Hanlin (Translator) ;

Ariadne Press, 2001

(Rottensteiner’s informative introduction :

“A Short History of Austrian Science Fiction“;

the short stories include

Martin Auer’s Time Travels;

Alfred Bittner’s Homo superior;

Kurt Bracharz’s Venice 2; Andreas Findig’s Godel’s Exit;

H.W. Franke’s Breath of the Sun;

Marianne Gruber’s The Invasion;

Peter Marginter’s The Machine;

Barbara Neuwirth’s The Character of the Huntress;

Heinz Riedler’s Cottage Industry;

Peter Schattschneider’s Banana Streams and The Jez’r Fragments; Michael Springer’s Ite missa est;

and Oswald Wiener’s The Bio-Adapter.

The Best Of Austrian Science Fiction aptly concludes with Rottensteiner’s “Notes on the Authors“).

“The Black Mirror and Other Stories : An Anthology of Science Fiction from Germany and Austria” – Franz Rottensteiner, editor; Mike Mitchell, translator ; (Early Classics of Science Fiction collection), Wesleyan University Press, 2008.

(Introduction : A Short History of Science Fiction in German ; The Pioneers: Science Fiction before World War I : Kurd Lasswitz -“To the Absolute Zero of Existence” (Germany, 1871) ; Kurd Lasswitz – “Apoikis” (Germany, 1882) ; Ludwig Hevesi – “Jules Verne in Hell” (Austria, 1906) ; Carl Grunert – “The Martian Spy” (Germany, 1908) ; Paul Scheerbart – “Malvu the Helmsman” (Germany, 1912) ; Between the World Wars : Otto Willi Gail – “The Missing Clock Hands” (Germany, 1929) ; Egon Friedell – “Is the Earth Inhabited?” (Austria, 1931) ; Hans Dominik – “A Free Flight in 2222” (Germany, 1934) ; German Science Fiction Comes into Its Own after World War II : Herbert W. Franke : “Thought Control” (Austria, 1961) ; Herbert W.Franke : “Welcome Home” (Austria, 1961) ; Herbert W.Franke – “Meteorites” (Austria, 1961) ; Ernst Vlcek – “Say It with Flowers” (Austria, 1980) ; Carl Amery -“Just One Summer” (Germany, 1985) ; Horst Pukallus – “The Age of Burning Mountains” (Germany, 1989) ; Science Fiction from the German Democratic Republic : Johanna Braun & Günter Braun – “A Visit to Parsimonia. A Scientific Report” (1981) ; Erik Simon – “The Black Mirror” (1983) ; Angela Steinmüller & Karlheinz Steinmüller – “The Eye That Never Weeps” (1984) ; The Current Generation: From the 1990s to the Present : Peter Schattschneider – “A Letter from the Other Side” (Austria, 1994) ; Wolfgang Jeschke – “Partners for Life” (Germany, 1996) ; Michael Marrak – “Astrosapiens” (Germany, 1998) ; Thorsten Küper -“Project 38 or the Game of Small Causes” (Germany, 2003) ; Michael K. Iwoleit – “Planck-Time” (Germany, 2004) ; Oliver Henkel – “Hitler on the Campaign Trail in America” (Germany, 2004) ; Helmuth W.Mommers -“Habemus Papam” (Austria, 2005) ; Andreas Eschbach – “Mother’s Flowers” (Germany, 2008) ; Editor’s Notes ; Selected Bibliography ; About the Author and Translator)

“Recent Writings on German Science Fiction,” Science Fiction Studies, Vol. 28, No. 2 (Jul., 2001), pp. 284–290.

“SF in Germany: A Short Survey,” Science Fiction Studies, Vol. 27, No. 1 (Mar., 2000), pp. 118–123.

“Science Fiction: Eine Einführung.” Insel Almanach auf das Jahr (1972): 5-21.

“Der Einsiedler von Providence. Lovecrafts ungewöhnliches Leben” (The Hermit of Providence. Lovecraft’s unusual life. (Collection of essays on H. P. Lovecraft), Phantastische Bibliothek. Band 290; = Suhrkamp-Taschenbuch 1626). Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 1992

“H. P. Lovecrafts kosmisches Grauen” (H. P. Lovecraft’s cosmic horror), Phantastische Bibliothek, Band 344; = Suhrkamp-Taschenbuch 2733). Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 1997

“Das Jahr 3000. Ein Zukunftstraum” Neuausgabe der Auflage von Jena 1897 in der Übersetzung von Willy Alexander Kastner ( The Year 3000. A future Dream. Reprint of 1897 Jena edition in the translation of Willy Alexander Kastner), Lüneburg 2012, coll. with Paolo Mantegazza & Dieter von Reeken

“Im Labor der Visionen. Anmerkungen zur phantastischen Literatur. 19 Aufsätze und Vorträge aus den Jahren 2000–2012” (In the Laboratory of Visions. Comments on the Fantastic Literature. 19 Essays and Lectures from the Years 2000-2012)

In German he has edited many anthologies of stories and essays about sf, including:

“Die Ratte im Labyrinth” (Rats in the Maze, anthology 1971);

the Polaris series, Polaris 1 (anthology 1973), #2 (anthology 1974),

a special Soviet sf issue, #3 (anthology 1975), #4 (anthology1978),

a French sf issue, #5 (anthology 1981), #6 (anthology 1982),

a Herbert W Franke issue, #7 ( anthology 1983), #8 (anthology 1985), #9 (anthology 1985),

old German sf, and #10 (anthology 1986),

a Strugatski issue; “Phantastiche Träume” (Fantastic Dreams, anthology 1983); “Phantastiche Welten” (Fantastic Worlds, anthology 1984);

Phantastiche Aussichten (Fantastic Sights, anth 1985);

Phantastiche Zeiten (Fantastic Times, anth 1986);

Lovecraft Lesebuch (Lovecraft Reader, anth 1987);

Seltsame Labyrinthe (Strange Labyrinths, anth 1987);

Der Eingang ins Paradies (The Door into Paradise, anth 1988);

Arche Noah (Noah’s Ark, anth 1989);

Die Sirene (The Siren, anth 1990);

Phantastiche Begegnungen (Fantastic Encounters)

SF anthologies in German:

◾Die Ratte im Labyrinth. Insel Verlag, 1971.

◾Pfade ins Unendliche. Insel Almanach auf das Jahr 1972. Insel Verlag, 1971.

◾Blick vom anderen Ufer. 1977.

◾Das Mädchen am Abhang. 1979.

◾Die andere Zukunft. 1982.

◾Das große Buch der Märchen, Sagen und Gespenster. Fischer, 1982.

◾Phantastische Träume. 1983.

◾Phantastische Welten. 1984.

◾Die Ermordung des Drachen. Insel Verlag, 1985.

◾Phantastische Aussichten. 1985.

◾Phantastische Zeiten. 1986.

◾Seltsame Labyrinthe. 1987.

◾Die dunkle Seite der Wirklichkeit. 1987.

◾Der Eingang ins Paradies. 1988.

◾Arche Noah. 1989.

◾Phantastische Begegnungen. 1990.

◾Die Sirene und andere phantastische Erzählungen. 1990.

◾Verführung. Eichborn Verlag, 1993.

◾Phantastisches aus Österreich. 1995.

◾Weltuntergänge en gros. Ablaufdatum 31.12.2000: Die Prophezeiungs-Falle. Aarachne Verlag, Wien 1999.

◾Weltuntergänge en detail. Ablaufdatum 31.12.2000: Die Prophezeiungs-Falle. Aarachne Verlag, Wien 1999.

◾mit Erik Simon: Tolkiens Geschöpfe. Heyne Verlag, 2003

Franz Rottensteiner at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

Disclaimer : All images used are for non-commercial illustrative purposes. The images used in this site’s posts are found from different sources all over the Internet, and are assumed to be in public domain and are displayed under the fair use principle.